Mandatory & Preferential Voting

In 2002 I spent a semester studying abroad in Adelaide, Australia. One of the classes I took at the University of Adelaide was an Introduction to Australian Politics. I enjoyed the course thoroughly; it led to me understanding the parliamentary system.

One aspect of Australian politics that stood out to me was that voting is mandatory in Australia. According to the BBC, Australia is one of only 23 countries worldwide with compulsory voting, and only ten that actively enforce it. Failing to vote is punishable by a fine. There is a debate in Australia if it works and if it is undemocratic. I believe that mandatory registration and voting would considerably improve our system here in the United States.

As citizens of a country, we enjoy many privileges, but we also need to meet our responsibilities. We desire the many freedoms granted to us in this country, but that does not give us the right to opt-out of that system's consequences. We may not agree with each law, but we have decided, through living here, that the system allows us to change these laws or accept the rule of that law.

Simply put: you have to pay your taxes.

There should be more than that: You should be required to vote. So much of who are leaders are is dependent on voter turnout or voter suppression. This battle has been going on since the country's founding with very limited enfranchisement, which has expanded dramatically, but perhaps not enough.

Candidates for political office should wine because an actual majority of citizens vote for them, not because a majority of those who choose to vote choose them. Mandatory voting would lead to dramatically different outcomes in certain jurisdictions and accurate representation.

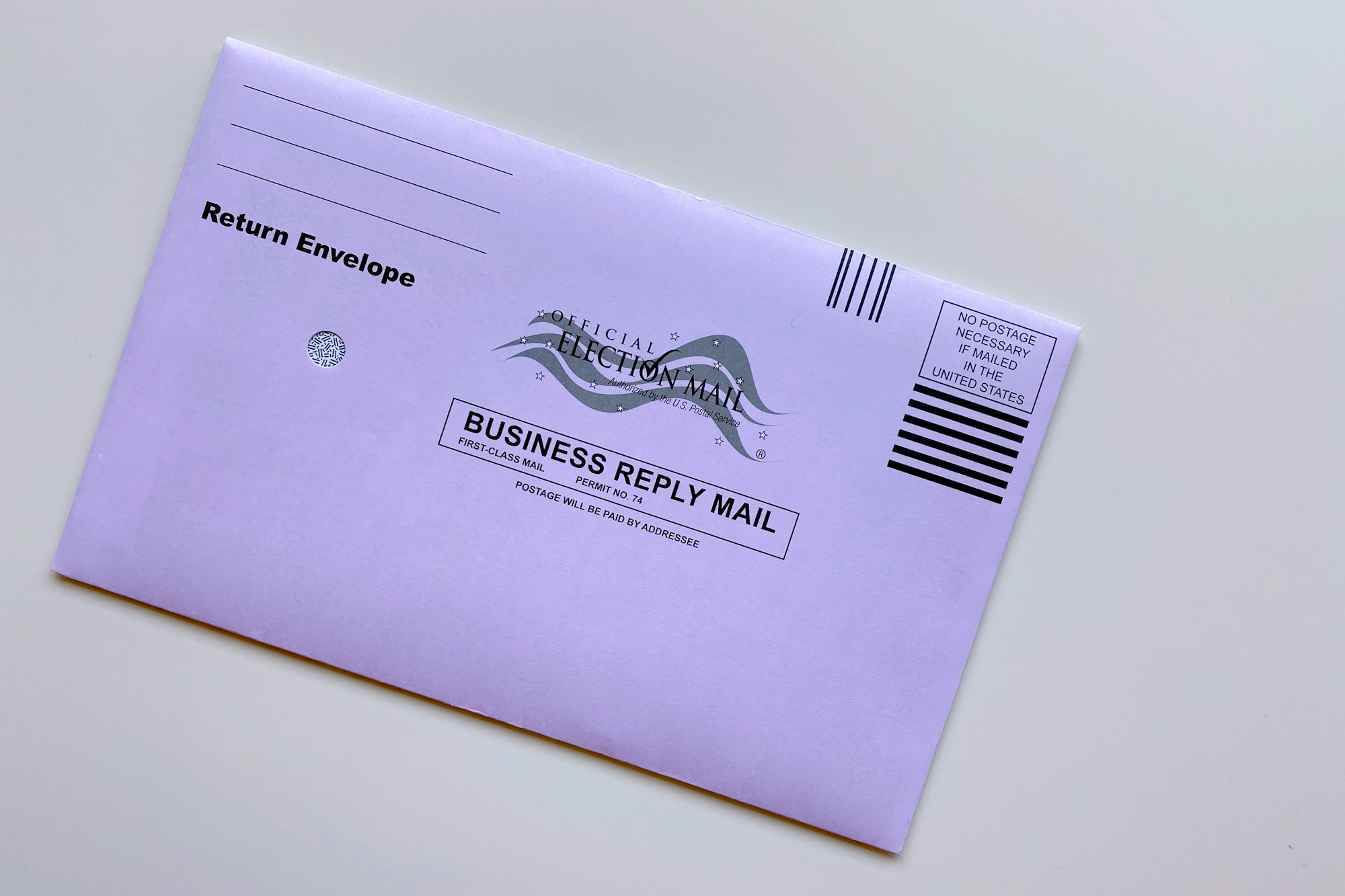

We can create a single national voting holiday each year (perhaps a Saturday instead of a Tuesday) to ensure that all citizens can vote. We can register all citizens to vote and require them to vote. A small ($10) fine can be levied to limit the economic consequence that shifts the perception from an optional choice to a required task.

People will undoubtedly continue not to vote (just as people speed or jaywalk), but more people will vote.

One of the complaints of those who choose not to vote is that they simply do not like the candidates, or they want to protest with their vote. This problem can be solved in part by greater participation in primary voting and through preferential voting.

Many voters feel limited by their choices in our two-party system. If you do not like either of the big-name candidates, you can vote for a third-party candidate. However, that may lead to your less-favored major party candidate winning. In a few years, candidates like Ross Perot or Jill Stein may have siphoned off enough votes to cause this shift.

When I was in high school, my congressional district (NM-3) had an election with a strong Green Party candidate. (The Green Party was very big in New Mexico at the time.) As a result of the more liberal vote splitting between the Green Party and the Democratic Party, the Republican candidate won, with around 1/3 of the vote.

That is not ideal.

With preferences, a voter can choose their first, second, or even third priority candidate. All first preference votes are counted, and the lowest vote count candidates are removed from consideration. Those voters ballots then have their second preference become their top preference. If there is still not a 50% + 1 winner, the process continues until there is.

Preferential voting is a simple solution allowing voters to say that yes, they prefer to vote for a Green Party candidate, but should that fail, they will vote for the Democrat (or the Republican).

Our democracy must continually evolve. We are not an agrarian society on the East Coast of North America any longer. We are a dynamic, 330M people strong, and geographically disparate society. Moving to better voting methods will enable us to achieve better the ideals laid out by our founders to have a representative democracy.